SSR Foreword

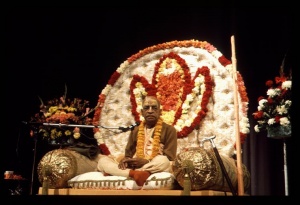

A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada

From the very start, I knew that His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupāda was the most extraordinary person I had ever met. The first meeting occurred in the summer of 1966, in New York City. A friend had invited me to hear a lecture by "an old Indian svāmī" on lower Manhattan's Bowery. Overwhelmed with curiosity about a svāmī lecturing on skid row, I went there and felt my way up a pitch-black staircase. A bell-like, rhythmic sound got louder and clearer as I climbed higher. Finally I reached the fourth floor and opened the door, and there he was.

About fifty feet away from where I stood, at the other end of a long, dark room, he sat on a small dais, his face and saffron robes radiant under a small light. He was elderly, perhaps sixty or so, I thought, and he sat cross-legged in an erect, stately posture. His head was shaven, and his powerful face and reddish horn-rimmed glasses gave him the look of a monk who had spent most of his life absorbed in study. His eyes were closed, and he softly chanted a simple Sanskrit prayer while playing a hand drum. The small audience joined in at intervals, in call-and-response fashion. A few played hand cymbals, which accounted for the bell-like sounds I'd heard. Fascinated, I sat down quietly at the back, tried to participate in the chanting, and waited.

After a few moments the svāmī began lecturing in English, apparently from a huge Sanskrit volume that lay open before him. Occasionally he would quote from the book, but more often from memory. The sound of the language was beautiful, and he followed each passage with meticulously detailed explanations.

He sounded like a scholar, his vocabulary intricately laced with philosophical terms and phrases. Elegant hand gestures and animated facial expressions added considerable impact to his delivery. The subject matter was the most weighty I had ever encountered: "I am not this body. I am not an Indian.... You are not Americans.... We are all spirit souls...."

After the lecture someone gave me a pamphlet printed in India. A photo showed the svāmī handing three of his books to Indian prime minister Lal Bahadur Shastri. The caption quoted Mr. Shastri as saying that all Indian government libraries should order the books. "His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta swami Prabhupāda is doing great work," the prime minister said in another small tract, "and his books are significant contributions to the salvation of mankind." I purchased copies of the books, which I learned the svāmī had brought over from India. After reading the jacket flaps, the small pamphlet, and various other literature, I began to realize that I had just met one of India's most respected spiritual leaders.

But I could not understand why a gentleman of such distinction was residing and lecturing in the Bowery, of all places. He was certainly well educated and, by all appearances, born of an aristocratic Indian family. Why was he living in such poverty? What in the world had brought him here? one afternoon several days later, I stopped in to visit him and find out.

To my surprise, Śrīla Prabhupāda (as I later came to call him) was not too busy to talk with me. In fact, it seemed that he was prepared to talk all day. He was warm and friendly and explained that he had accepted the renounced order of life in India in 1959, and that he was not allowed to carry or earn money for his personal needs. He had completed his studies at the University of Calcutta many years ago and had raised a family, and then he had left his eldest sons in charge of family and business affairs, as the age-old vedic culture prescribes. After accepting the renounced order, he had arranged a free passage on an Indian freighter (Scindia Steamship Company's Jaladuta) through mutual friends. In September 1965, he had sailed from Bombay to Boston, armed with only seven dollars' worth of rupees, a trunk of books, and a few clothes. His spiritual master, His Divine Grace Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī Ṭhākura, had entrusted him with delivering India's vedic teachings to the English-speaking world. And this was why, at age sixty-nine, he had come to America. He told me he wanted to teach Americans about Indian music, cooking, languages, and various other arts. I was mildly amazed.

I saw that Śrīla Prabhupāda slept on a small mattress and that his clothes hung on lines at the back of the room, where they were drying in the summer afternoon heat. He washed them himself and cooked his own food on an ingenious utensil he had fashioned with his own hands in India. In this three-layer apparatus he cooked three preparations at once. Stacked all around him and his ancient-looking portable typewriter in another section of the room were seemingly endless manuscripts. He spent almost all of his waking hours—about twenty in twenty-four, I learned—typing the sequels to the three volumes I had purchased. It was a projected sixty-volume set called the Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam, and virtually it was the encyclopedia of spiritual life. I wished him luck with the publishing, and he invited me back for Sanskrit classes on Saturdays and for his evening lectures on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday. I accepted, thanked him, and left, marveling at his incredible determination.

A few weeks later—it was July 1966—I had the privilege of helping Śrīla Prabhupāda relocate in a somewhat more respectable neighborhood, on Second Avenue. Some friends and I pitched in and rented a ground-floor storefront and a second-floor apartment, to the rear of a little courtyard, in the same building. The lectures and chanting continued, and within two weeks a rapidly growing congregation was providing for the storefront (by this time a temple) and the apartment. By now Śrīla Prabhupāda was instructing his followers to print and distribute leaflets, and the owner of a record company had invited him to record an LP of the Hare Kṛṣṇa chant. He did, and it was a huge success. In his new location he was teaching chanting, Vedic philosophy, music, japa meditation, fine art, and cooking. At first he cooked—he always taught by example. The results were the most wonderful vegetarian meals I had ever experienced. (Śrīla Prabhupāda would even serve everything out himself!) The meals usually consisted of a rice preparation, a vegetable dish, capātīs (tortilla-like whole-wheat patties), and dāl (a zestfully spiced mung bean or split pea soup). The spicing, the cooking medium—ghee, or clarified butter—and the close attention paid to the cooking temperature and other details all combined to produce taste treats totally unknown to me. Others' opinions of the food, called prasādam ("the Lord's mercy"), agreed emphatically with mine. A Peace Corps worker who was also a Chinese-language scholar was learning from Śrīla Prabhupāda how to paint in the classical Indian style. I was startled at the high quality of his first canvases.

In philosophical debate and logic Śrīla Prabhupāda was undefeatable and indefatigable. He would interrupt his translating work for discussions that would last up to eight hours. Sometimes seven or eight people jammed into the small, immaculately clean room where he worked, ate, and slept on a two-inch-thick foam cushion. Śrīla Prabhupāda constantly emphasized and exemplified what he called "plain living and high thinking." He stressed that spiritual life was a science provable through reason and logic, not a matter of mere sentiment or blind faith. He began a monthly magazine, and in the autumn of 1966 The New York Times published a favorable picture story about him and his followers. Shortly thereafter, television crews came out and did a feature news story.

Śrīla Prabhupāda was an exciting person to know. Whether it was out of my desire for the personal benefits of yoga and chanting or just out of raw fascination, I knew I wanted to follow his progress every step of the way. His plans for expansion were daring and unpredictable—except for the fact that they always seemed to succeed gloriously. He was seventyish and a stranger to America, and he had arrived with practically nothing, yet now, within a few months, he had single-handedly started a movement! It was mind-boggling.

One August morning at the Second Avenue storefront temple, Śrīla Prabhupāda told us, "Today is Lord Kṛṣṇa's appearance day." We would observe a twenty-four-hour fast and stay inside the temple. That evening some visitors from India happened along. One of them—practically in tears—described his unbounded rapture at finding this little piece of authentic India on the other side of the world. Never in his wildest dreams could he have imagined such a thing. He offered Śrīla Prabhupāda eloquent praise and deep thanks, left a donation, and bowed at his feet. Everyone was deeply moved. Later, Śrīla Prabhupāda conversed with the gentleman in Hindi, and since what he was saying was unintelligible to me, I was able to observe how his every expression and gesture communicated to the very core of the human soul.

Later that year, while in San Francisco, I sent Śrīla Prabhupāda his first airline ticket, and he flew out from New York. A sizable group of us greeted him at the terminal by chanting the Hare Kṛṣṇa mantra. Then we drove him to the eastern edge of Golden Gate Park, to a newly rented apartment and storefront temple—an arrangement very similar to that in New York. We had established a pattern. Śrīla Prabhupāda was ecstatic.

A few weeks later the first mṛdaṅga (a long clay drum with a playing head on each end) arrived in San Francisco from India. When I went up to Śrīla Prabhupāda's apartment and informed him, his eyes opened wide, and in an excited voice he told me to go down quickly and open the crate. I took the elevator, got out on the ground floor, and was walking toward the front door when Śrīla Prabhupāda appeared. So eager was he to see the mṛdaṅga that he had taken the stairway and had beaten the elevator. He asked us to open the crate, he tore off a piece of the saffron cloth he was wearing, and, leaving only the playing heads exposed, he wrapped the drum with the cloth. Then he said, "This must never come off," and he began giving detailed instructions on how to play and care for the instrument.

Also in San Francisco, in 1967, Śrīla Prabhupāda inaugurated Ratha-yātrā, the Festival of the Chariots, one of several festivals that, thanks to him, people all over the world now observe. Ratha-yātrā has taken place in India's Jagannātha Purī each year for two thousand years, and by 1975 the festival had become so popular with San Franciscans that the mayor issued a formal proclamation—"Ratha-yātrā Day in San Francisco."

By late 1966 Śrīla Prabhupāda had begun accepting disciples. He was quick to point out to everyone that they should think of him not as God but as God's servant, and he criticized self-styled gurus who let their disciples worship them as God. "These 'gods' are very cheap," he used to say. One day, after someone had asked, "Are you God?" Śrīla Prabhupāda replied, "No, I am not God—I am a servant of God." Then he reflected a moment and went on. "Actually, I am not a servant of God. I am trying to be a servant of God. A servant of God is no ordinary thing."

In the mid-seventies Śrīla Prabhupāda's translating and publishing intensified dramatically. Scholars all over the world showered favorable reviews on his books, and practically all the universities and colleges in America accepted them as standard texts. Altogether he produced some eighty books, which his disciples have translated into twenty-five languages and distributed to the tune of fifty-five million copies. He established one hundred eight temples worldwide, and he has some ten thousand initiated disciples and a congregational following in the millions. Śrīla Prabhupāda was writing and translating up to the last days of his eighty-one-year stay on earth.

Śrīla Prabhupāda was not just another oriental scholar, guru, mystic, yoga teacher, or meditation instructor. He was the embodiment of a whole culture, and he implanted that culture in the West. To me and many others he was first and foremost someone who truly cared, who completely sacrificed his own comfort to work for the good of others. He had no private life, but lived only for others. He taught spiritual science, philosophy, common sense, the arts, languages, the Vedic way of life—hygiene, nutrition, medicine, etiquette, family living, farming, social organization, schooling, economics—and many more things to many people. To me he was a master, a father, and my dearmost friend.

I am deeply indebted to Śrīla Prabhupāda, and it is a debt I shall never be able to repay. But I can at least show some gratitude by joining with his other followers in fulfilling his innermost desire—publishing and distributing his books.

"I shall never die," Śrīla Prabhupāda once said. "I shall live forever in my books." He passed away from this world on November 14, 1977, but surely he will live forever.

Michael Grant

(Mukunda dāsa)